Monitor Important Things

Monitor Important Things

How do you know your application is running? How do you know your application is running at peak performance? How do you know your application is running at peak performance without wasting money on unnecessary infrastructure or costs?

Application Monitoring using application metrics can help answer these questions. With effective application monitoring, you can also analyze long-term trends, compare over time or experiment groups, and build the foundation for dashboards, alerts, and logging.

In this post, we write two examples in Python from the book, ‘Python for DevOps’ by Noah Gift, Kennedy Behrman, Alfredo Deza, and Grig Gheorghiu. We create two files, web.py and metrics.py. In the web.py file, we use prometheus_client to count the number of requests on the base URL /. We also use prometheus_client to create a histogram to enumerate slow database requests from the /database URL. In the metrics.py file, we define the counter and use StatsD to push the metrics to graphite. These two examples help start the monitoring framework for your application or service.

The first URL is the prometheus-backed flask application

http://127.0.0.1:5000/ - Displays Development Prometheus-backed Flash App

The second URL is designed to fake a long database query we can monitor

http://127.0.0.1:5000/database/ - Displays Completed expensive database operation

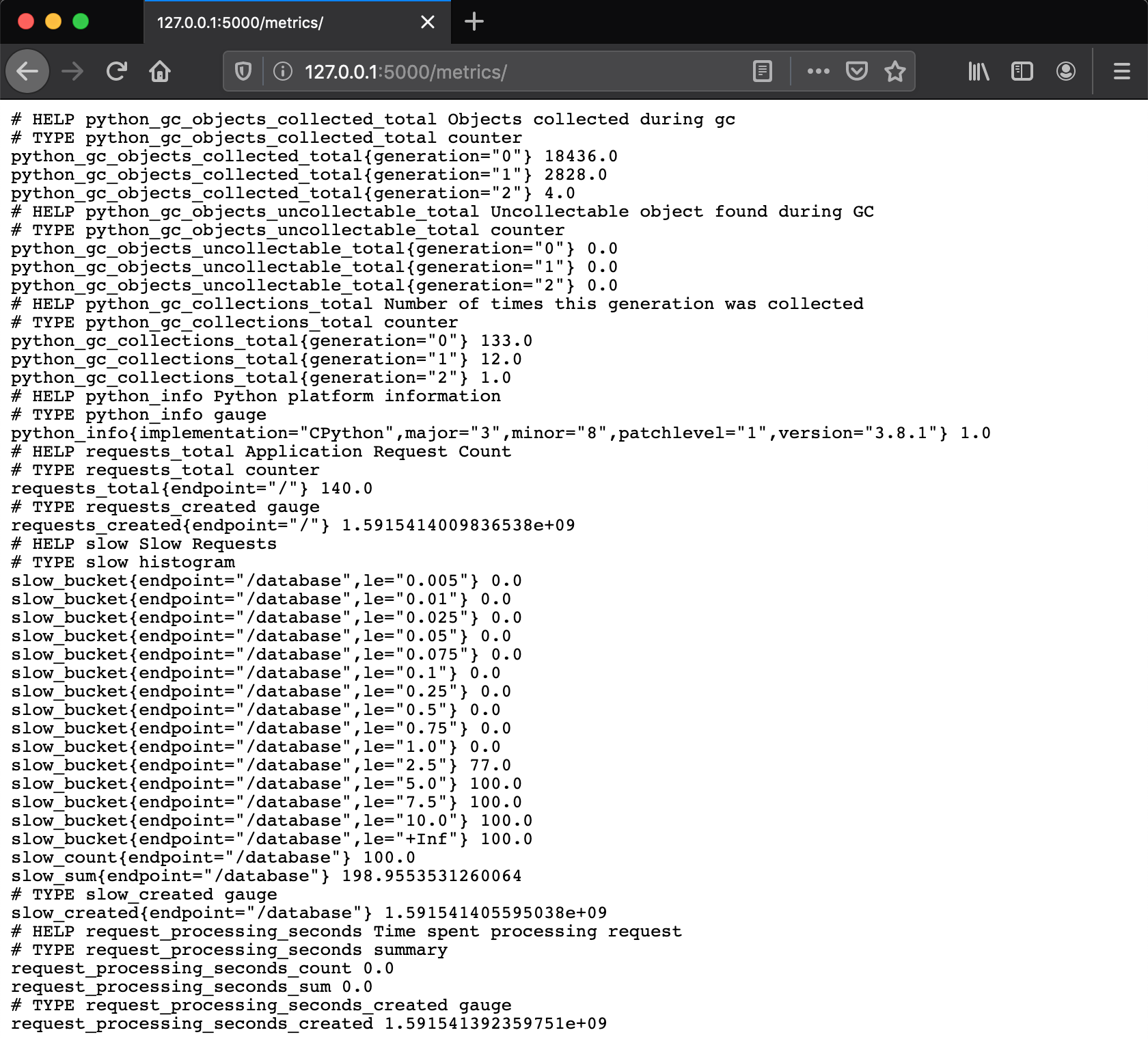

The third URL displays our application metrics http://127.0.0.1:5000/metrics/ - Displays application metrics

To run this code, clone the repo locally and run this command

FLASK_APP=web.py flask run

The expected output includes

$ FLASK_APP=web.py flask run

* Serving Flask app "web.py"

* Environment: production

WARNING: Do not use the development server in a production environment.

Use a production WSGI server instead.

* Debug mode: off

* Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000/ (Press CTRL+C to quit)

To validate this code, navigate your web browser to three URL’s, in this order

The expected output includes

- http://127.0.0.1:5000/ - Displays

Development Prometheus-backed Flash App - http://127.0.0.1:5000/database/ - Displays

Completed expensive database operation - http://127.0.0.1:5000/metrics/ - Displays list of application metrics that now includes both

total number of requestsandnumber of slow database requests

Screenshot of the http://127.0.0.1:5000/metrics/ page

Example of expected output for total number of requests on the baseURL at http://127.0.0.1:5000/

# TYPE requests_total counter

requests_total{endpoint="/"} 20.0

Example of expected output for the number of slow database requests as determined by http://127.0.0.1:5000/database/

# TYPE slow histogram

slow_count{endpoint="/database"} 6.0

web.py

from flask import Response, Flask

import prometheus_client

import time

import random

from prometheus_client import Counter

from prometheus_client import Histogram

app = Flask('prometheus-app')

@app.route('/metrics/')

def metrics():

return Response(

prometheus_client.generate_latest(),

mimetype='text/plain; version=0.0.4; charset=utf-8'

)

REQUESTS = Counter(

'requests', 'Application Request Count',

['endpoint']

)

@app.route('/')

def index():

REQUESTS.labels(endpoint='/').inc()

return '<h1>Development Prometheus-backed Flash App</h1>'

TIMER = Histogram(

'slow', 'Slow Requests',

['endpoint']

)

@app.route('/database/')

def database():

with TIMER.labels('/database').time():

time.sleep(random.uniform(1, 3))

return '<h1>Completed expensive database operation</h1>'

from prometheus_client import start_http_server, Summary

# Create a metric to track time spent and requests made.

REQUEST_TIME = Summary('request_processing_seconds', 'Time spent processing request')

# Decorate function with metric.

@REQUEST_TIME.time()

def process_request(t):

"""A dummy function that takes some time."""

time.sleep(t)

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Start up the server to expose the metrics.

start_http_server(8000)

# Generate some requests.

while True:

process_request(random.random())

metrics.py

import statsd

import get_prefix

def Counter(name):

return statsd.Counter("%s.%s" % (get_prefix(), name))

from metrics import Counter

counter = Counter(__name__)

counter +=1

Most Monitoring services fall into two categories: Pull services or Push services. Knowing whether pull or push is a better choice for a particular situation is valuable. Noah et al. show us examples with Graphite and StatsD for Push and Prometheus for Pull in the book, “Python for DevOps”.

Prometheus is a great choice for short-lived data or data that frequently changes; whereas Graphite is better suited for long-term historical information.

This application uses python to create a Flask web application and three URL’s. At the base URL /, we use prometheus_client to add the counter: requests with the description: Application Request Count, and the label: endpoint. We also use a histogram: slow with the description: Slow Requests. At the /metrics route, we use prometheus_client to generate the latest response from the counter. From the /database route we simulate an expensive database operation, tracking the start time and end time, and sending them to a histogram with prometheus_client.

When choosing application metrics, the Four Golden Signals from Google’s Site Reliability Engineering Book gives me confidence my service or application has monitoring enough coverage. The Four Golden Signals are Latency, Traffic, Errors, and Saturation.

| Four Golden Signals | Definition |

|---|---|

| Latency | The time is takes to service a request |

| Traffic | A measure of how much demand is being placed on your system |

| Errors | Rate of requests that fail, either explicitly (e.g., HTTP 500s), implicitly (for example, an HTTP 200 success response, but coupled with the wrong content), or by policy (for example, “If you committed to one-second response times, any request over one second is an error”). |

| Saturation | A measure of how “full” your system is. A measure of your system fraction, emphasizing the resources that are most constrained (e.g., in a memory-constrained system, show memory; in an I/O-constrained system, show I/O). |

Another great point from the Google SRE book, is knowing What is broken and Why maps to Symptoms versus Cause.

| What (Symptoms) | Why (Cause) |

|---|---|

| 400 or 500 errors | Database severs are refusing connections |

| application response times slow | AWS SNS queue is not decreasing fast enough |

I hope this post and these code examples help you build understanding of application monitoring and the foundation for dashboards, alerts, and logging.

References

Link to my GitHub repo for the code in this post https://github.com/icefelt/python_prometheus_graphite_examples

This code is from the Monitoring and Logging chapter of the “Python for DevOps” book by Noah Gift, Kennedy Behrman, Alfredo Deza, and Grig Gheorghiu. You can buy this book on Amazon

I used learnings from the Monitoring Distributed Systems Chapter of Google’s “Site Reliability Engineering” book by Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, and Niall Murphy. You can read it online here: https://landing.google.com/sre/sre-book/toc/. You can also buy this book on Amazon